By Victor Bwire

In just a span of two weeks, I have encountered several cases involving content theft, plagiarism, and copyright infringement by digital media outlets. The use of pirated content, cut-and-paste methods, or using stolen content without acknowledging the original owner has become widespread.

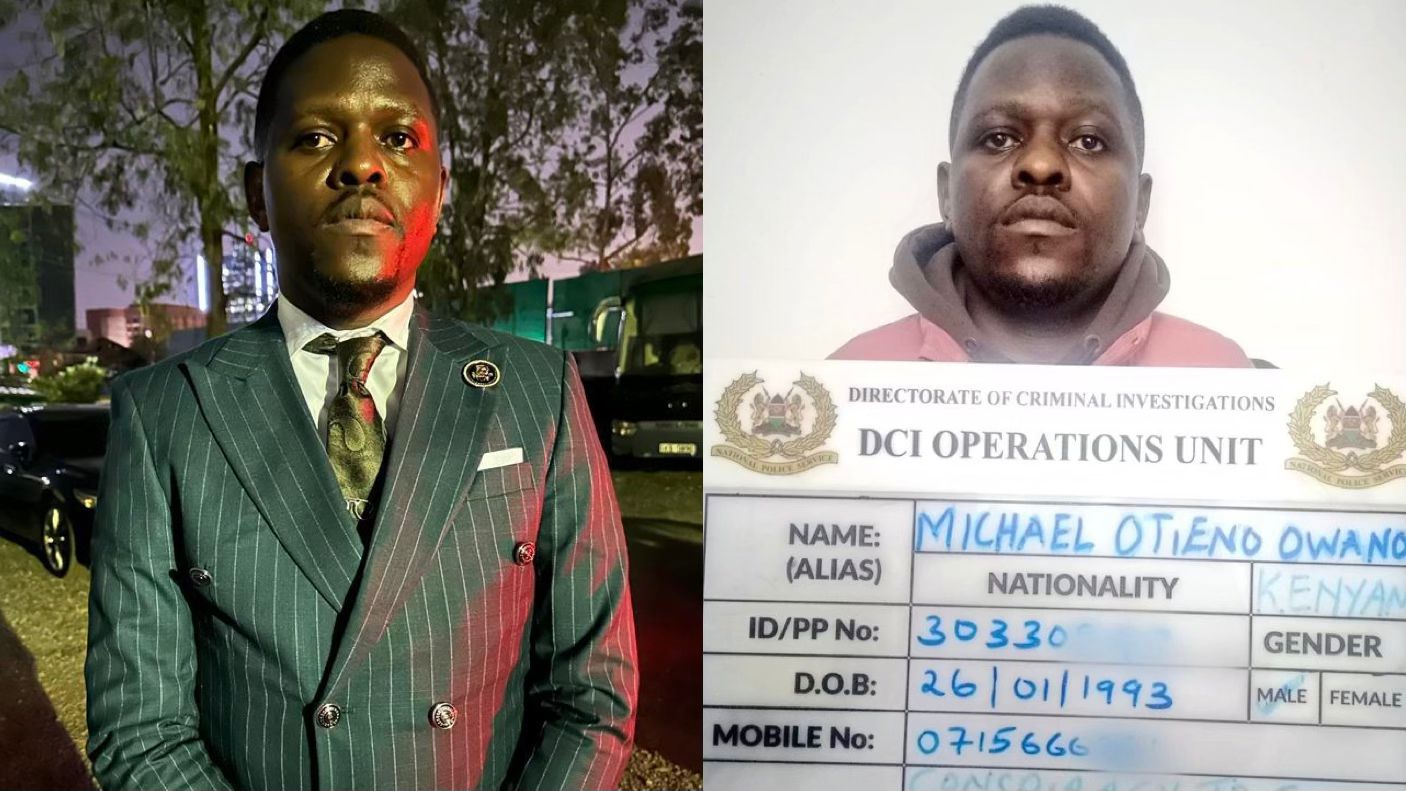

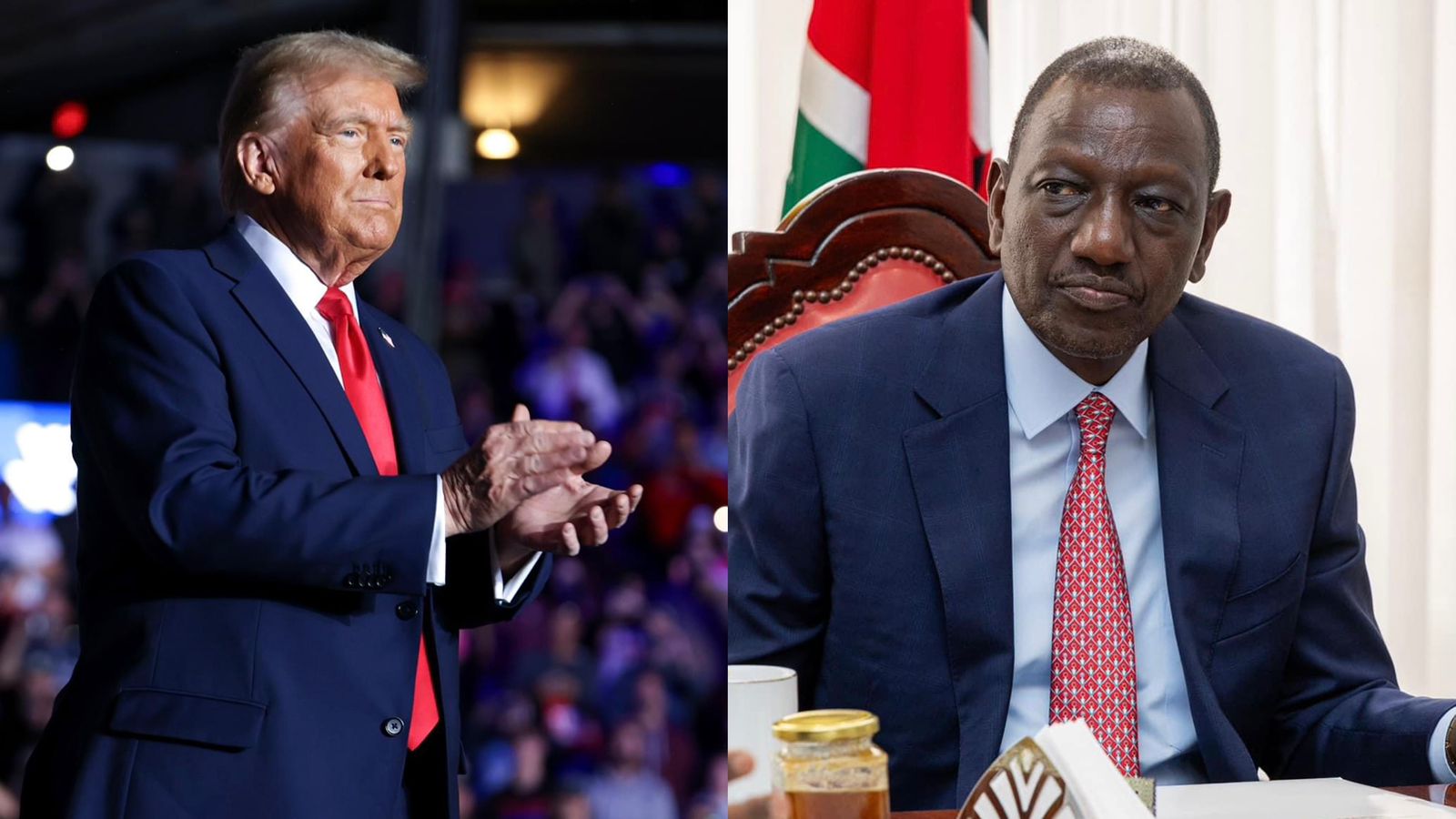

As has been the trend in Kenya over the years, the rise of online media usage has not come without our perennial problems: tribalism, insults, and a lack of decorum. Because of this, the use of online media platforms has attracted new laws and administrative codes aimed at regulating online journalism. Suddenly, we are witnessing a crackdown on irresponsible online media users, including bloggers who now face new charges, such as undermining the authority of public officers and, in some cases, hate speech.

Read More

Online platforms have opened opportunities for content creation, especially for people who did not necessarily go through conventional journalism training. These individuals are good at producing news, highly focused, and making money, but they often remain unaware of basic ethical standards and legal requirements in the sector. As a result, they expose their outlets to significant legal challenges, including defamation, copyright infringement, and data/privacy litigation.

The most common issue now is content theft, which puts them in conflict with the law. While some attempt to engage in unethical practices such as manipulating or concealing content, information, audio, or video, these efforts have not resolved the underlying problems.

Although digital publishing has introduced challenges globally, professional ethics remain the same as those in traditional publishing. The obligation to respect the rule of law in online publishing persists. In fact, it is becoming even more difficult as the space for freedom of expression is increasingly subject to legal constraints.

As Professor Ben Sihanya notes, the transmission of broadcasting has raised several questions regarding intellectual property (IP), particularly related to digital copyright, trademarks, and the domain name system. In Kenya, such matters are protected and arbitrated under the Copyright Act of 2001, but more and more people are seeking redress through the Media Council of Kenya. Section 22 of the Act lists copyrightable works as (a) literary works, (b) musical works, (c) artistic works, (d) audio-visual works, (e) sound recordings, and (f) broadcasts. Section 2 provides examples under these categories.

In his article, "Media Law in Kenya in the Era of Digital Migration," Professor Sihanya points out that digital work is protected under copyright if it is original and expressed in a tangible, material, or fixed form. He explains that the Act implicitly defines originality as "sufficient effort having been expended on making the work to give it an original character." Tangibility refers to "a work that has been written down, recorded, or otherwise reduced to material form."

Copyright law protects and promotes the expression of ideas, including information, facts, data, formulas, knowledge, or concepts. It safeguards the intellectual and economic interests of creators, owners, assignees, (sub) licensees, and publishers of literary, artistic, musical, audio-visual works, and broadcasts.

Digital tools such as X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, Facebook, Flickr, and YouTube have revolutionized the way people communicate, allowing individuals to "tell" their own stories by bypassing traditional information gatekeepers.

There is a lot happening on online media platforms in terms of sharing information, breaking news, and expanding the boundaries of information exchange. Kenya, like many other countries, is experiencing the effects of new technology on its media landscape.

-1720258272.jpg)

Several online content producers have emerged, particularly bloggers whose style of writing and content often disregard established codes of ethics. While online news production and dissemination offer enormous opportunities for educating Kenyans and promoting peaceful coexistence, if left unchecked, they can have negative impacts. While some online platforms have been sources of positive information, many others have not.

This has prompted policymakers, including the police through the cybercrime department, to start scrutinizing blogs and online platforms. Several bloggers have flouted all known journalism ethics, posting content that borders on hate speech and invasion of privacy. Some of the postings lack objectivity, accuracy, and fail to provide fair comment on matters of public interest.

The Code of Ethics for the Practice of Journalism cautions the media against intruding into an individual’s private life without consent unless it is in the public interest. The same article states that public interest must be legitimate, meaning well-defined and not driven by mere curiosity. It is expected that online journalists adhere to the same code of ethics that guides traditional journalists. Digital content producers must observe professional ethics just like other professionals.

Aware of the challenges posed by new platforms, many media enterprises in Kenya have developed social media and blogging policies for their journalists to ensure that even in their private lives, they maintain professionalism and uphold the credibility of their organizations.

Content and news producers must remain professional and follow basic requirements, such as acknowledging the original creators of materials they are using, paying for content they didn’t produce, or developing agreements with content owners. For instance, consider the English Premier League matches broadcast by several FM stations across the country without permission. Such actions violate copyright laws.

-1726720406.jpg)

-1700476031.jpg)

-1730900214.jpg)