By Victor Bwire

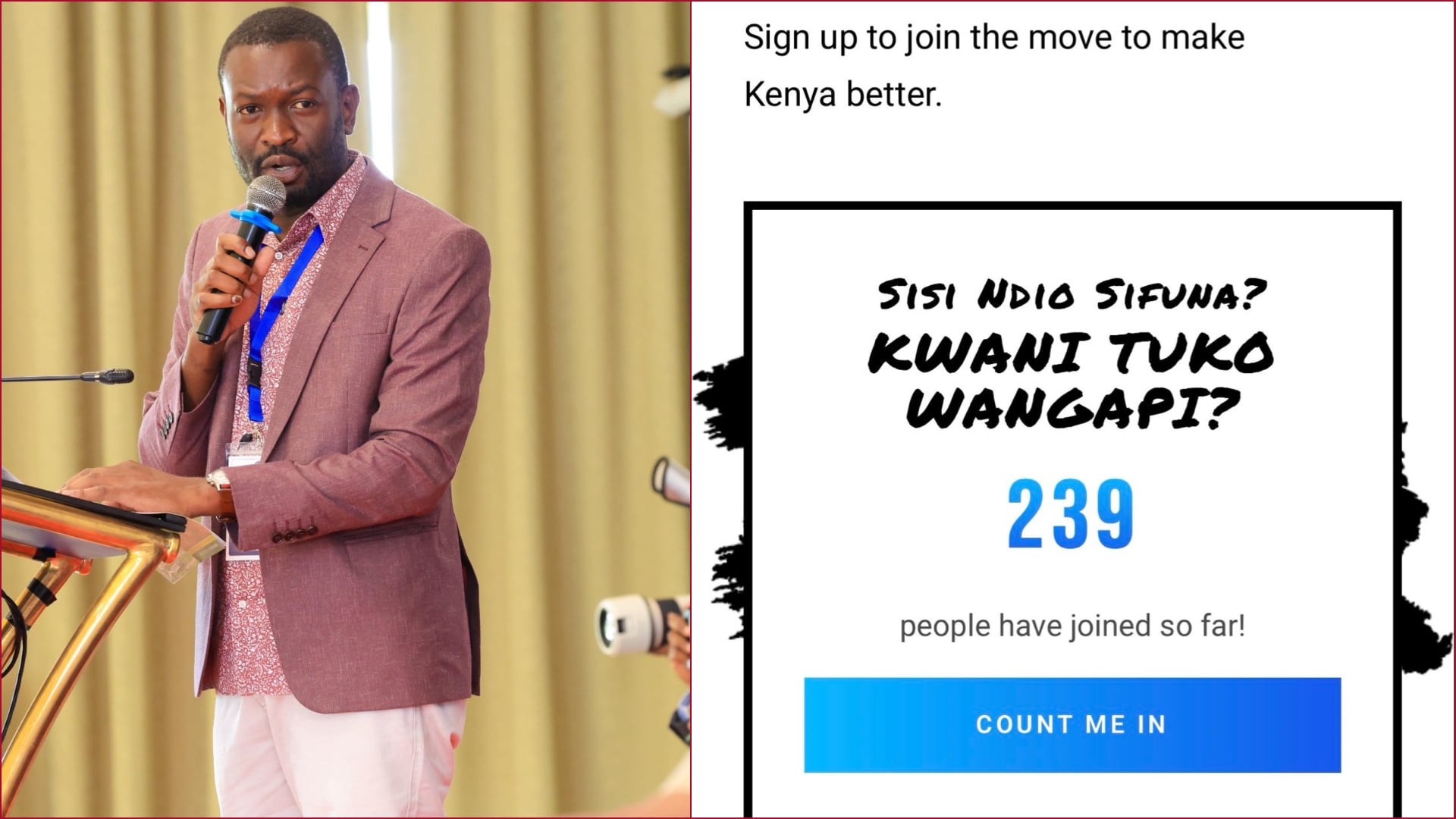

The June 2024 public protests in Kenya against governance issues highlighted the importance of citizen-led efforts to create and consume media content.

Through effective mass mobilization on digital platforms, the organization of the country-wide public demonstrations demonstrated the significance of social media in fostering conversations on national issues. These events underscored the need for the country to reconsider its regulatory approach to the media and communication space.

The current regulatory framework does not meet the needs of the media and communication sector. The era of old policymakers sitting in boardrooms and creating laws and administrative codes to regulate or determine the media content people generate or consume, whether harmful or useful, is long gone.

Even the notion of self-regulation in the traditional sense is now outdated. These policymakers tend to make laws and administrative codes for the old/traditional media they are accustomed to, while media operations and consumption trends have evolved. This discrepancy renders the laws outdated almost immediately.

Read More

The digital platforms and their user-generated content approach have democratized the media and communication space to the extent that pure government control or voluntary self-regulation is insufficient. It now calls for multi-player or coalition arrangements that bring together governments, platform providers, journalists, civil society, regulators, and other non-state actors through loose stakeholder structures.

.jpg)

The gatekeepers in the media and communication space in the country, just like in the rest of the world, have tremendously changed. An earlier study by the Media Council of Kenya on the impact of technology on media practice in Kenya established: 'Access to mobile and digital technologies and their increasing application in Kenya have had numerous consequences on media production, dissemination, reception, and consumption.

From a consumer perspective, it is abundantly clear that their consumption of, and interactions with media is enriched thanks to technology. Ordinary people can participate in media productions. The developments mean they can consume and produce content (user-generated content, and now they are aptly referred to as prosumers) and sometimes inform. This active involvement means they can challenge mainstream media dominance.

Some marginalized communities or those who feel their issues are hardly given space in mainstream media, can utilize technologies to articulate their concerns. The rise of citizen journalism is built on such premises. Additionally, consumers can now be more demanding of media, wanting information or products that are relevant to them.

Online communication tools such as X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, Facebook, Flickr, and YouTube have changed the way conversations happen in Kenya. People previously unable to join national conversations in media spaces are now increasingly involved in the media business by creating content, conducting mass mobilization, and contributing stories, pictures, and audio-visual material for publication by mainstream media.

This has led to the growing practice of what is commonly referred to as digital or networked journalism. In essence, people can easily ‘tell’ their own stories by sidestepping information gatekeepers or middlepersons who once controlled information and media products.

A number of scholars (Bakker and Sadaba, 2008; Steur, 1994: 84; and Jensen, 1998: 201) have discussed how digital technologies have offered users numerous opportunities and the power to determine what they want to consume. They highlight 'the extent to which the user can participate in modifying the form and content of a mediated environment in real time' and 'allow the user to exert influence on the content or form of the mediated communication.'

Beyond the traditional fear of harmful content and disinformation through digital media platforms, the increasing enactment of data protection, privacy, and copyright laws on the continent necessitates enhanced data literacy activities.

Truth in the era of technology is suffering the most, and existing regulations and practices seem unable to manage the situation. We need new approaches to address this issue, especially media and digital literacy, rather than a fixation on developing new laws that threaten freedom of expression.

Nations are calling disinformation, or foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI), a global crisis, comparable to climate change, radicalization, and world financial crises affecting humanity. A modest approach to digital ecosystem regulation is insufficient to solve the problem, and merely citing community rules and removing disinformation or hate speech is no longer convincing or adequate.

Governments and players in the sector must engage with digital platforms to become educated and skilled in the technical aspects of technology to engage in meaningful content regulation.

Without in-depth and proper training, most people will still be at the mercy of tech companies that only provide community rules. We must shift our focus from merely content moderation to tech accountability to ensure the responsible and beneficial use of digital platforms.

Mr Victor Bwire is the Head of Media Development and Strategy at the Media Council of Kenya.